One night in Texas in December 2019, as the NBA’s analytics era entered full bloom, Rick Carlisle summarized the new order’s negative view of a basic basketball play.

Post-ups were once a staple of plodding, inside-out offenses across the league, but by 2019, they’d been declining in frequency for years. Yet that didn’t stop the TV commentators that night from wondering why Kristaps Porzingis wasn’t playing with his back to the basket more, in the long tradition of elite NBA big men.

In a memorable postgame rant, Carlisle, then Porzingis’ coach on the Dallas Mavericks, explained why. «The post-up’s not a good play anymore,» he said. «It’s just not a good play. It’s not a good play for a 7-foot-3 guy. It’s a low-value situation.

«We’ve got to realize,» Carlisle finished, «that this game has changed.»

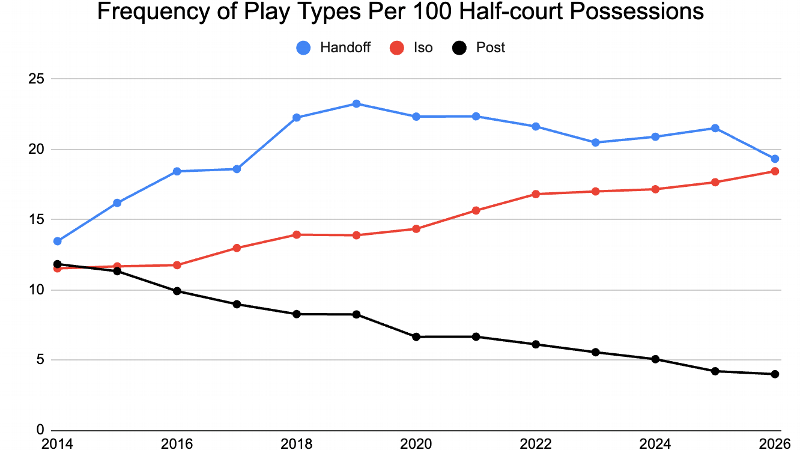

Indeed, the NBA was in the midst of massive strategic changes at the end of the 2010s, and the post-up was a chief casualty. In 2013-14, the first season of GeniusIQ tracking data, teams averaged 11.8 post-ups per 100 half-court possessions — about the same as isolations and handoffs. But while the frequency of isos and handoffs has increased by more than 50% since then, post-ups have declined by two-thirds, to just 4.0 per 100 half-court possessions in 2025-26.

Yet a strange reversal occurred in the mid-2020s. To twist Carlisle’s words, the game has changed back: What was once decried as an inefficient, low-value play has instead become the most efficient half-court play in the sport — better than isolations, better than handoffs, even better than the good old pick-and-roll.

The post-up won’t — and shouldn’t — ever return to the forefront of offensive basketball strategy. But the play’s fall and rise reflect broader lessons about how the sport has changed, and changed again, and will keep changing. It’s a vehicle for stars such as Nikola Jokic, Victor Wembanyama and Cade Cunningham to show off their exquisite footwork and one-on-one dominance. And it’s also, at its simplest, a way to beat modern defenses and win games.

The post-up is «deadly,» longtime practitioner DeMar DeRozan said, «when you know how to use it the right way.»

(All post-up data in this piece comes from GeniusIQ tracking.)

The post-up’s mathematical trick

Porzingis reclined in the visitors locker room in Chicago, following a 27-point effort in an Atlanta Hawks loss, and grinned when asked about Carlisle’s rant from six years ago. «I do remember that,» he said, and paused before making an admission: «He was right.»

In retrospect, the veteran center knows his numbers weren’t good enough to command post touches in Dallas. During the 2019-20 season, the Mavericks averaged just 0.92 points when Porzingis posted up and either shot, drew a foul, committed a turnover or passed to a shooter, which ranked 37th out of 46 players with at least 100 post-ups.

But more recently, in Washington, Boston and now Atlanta, a devotion to training and analytics boosted Porzingis’ effectiveness in the post. He grudgingly accepted that his height wasn’t enough to score consistently down low; instead, he learned to lean into his strengths — such as finding the right angles for bank shots — and became a foul-drawing master.

Since the start of the 2022-23 season, Porzingis is up to 1.26 points per post-up — the best mark out of 54 players with at least 200 posts in that span.

«If [Carlisle] said that now,» Porzingis said, «he would probably be wrong.»

While Porzingis represents the most extreme example, post-up improvement is a leaguewide phenomenon. In the first three seasons of tracking data in the mid-2010s, plays featuring a post-up at any point averaged just 89 points per 100 chances. Since 2022-23, however, that number is 103 points per 100 chances — about four ticks higher than the average half-court play overall.

This season, that gap is even wider: 103.9 points per 100 plays with a post-up versus 99.0 points per 100 half-court plays overall, a difference of 4.9 points.

Put another way: If a team scored 103.9 points per 100 half-court chances, it would rank fifth in the NBA this season.

That’s not to suggest that an all-post offense would actually be one of the best in the league. Rather, post-up efficiency has risen in large part because of selection bias. It’s a sort of mathematical trick: If only the best post-up scorers are still using the play regularly, then its average outcome should improve.

«Only stars!» one Eastern Conference executive said when asked which players should be trusted to post up regularly.

The relative scarcity of post-ups in today’s NBA means that one star player can singlehandedly skew leaguewide numbers. Last season, Jokic used 5.7% of the entire league’s post-ups all by himself. For comparison, the league leaders in isolations (Shai Gilgeous-Alexander) and pick-and-rolls (Trae Young) were at just 2% of their proportion of those play types.

And Jokic was so dominant in such a large share of post-ups that he alone raised the entire league’s post-up efficiency by 1.1 points per 100 possessions.

This relationship between falling post-up frequency and rising post-up efficiency reveals the trend’s first broad lesson: Stars play by different rules, and rather than dictate a one-size-fits-all strategy, analytics work best when they account for individual player profiles.

«If you’ve got guys that are uniquely gifted,» Detroit Pistons coach J.B. Bickerstaff said, «you’ve got to try your best to put them in positions of strength, even if it may be a zag from what the rest of the league is doing.»

That’s the case in Atlanta, where Porzingis is in his first season. In nine out of Quin Snyder’s 10 full seasons as an NBA head coach, his teams in Utah and Atlanta finished 25th or lower in post-up frequency. The Hawks ranked 29th last season.

But that was more of a reflection of personnel than a strict personal philosophy: Snyder wanted to get the ball in the paint and pressure the basket by whatever means he could. «No disrespect to Rudy Gobert, but he was our post threat, so we’d been a pick-and-roll team,» Snyder said of his time in Utah.

Porzingis is different. Even with no other Hawk averaging more than one post-up per game, Atlanta is up to 15th in post frequency this season because Porzingis deserves so many touches down low.

This distinction is similar to how teams’ use of the midrange has shifted in the analytics era. Generally speaking, teams take fewer midrange shots in the 2020s than in previous decades — but that decline has been concentrated among role players, while stars such as Gilgeous-Alexander, Kevin Durant and Devin Booker are still free to pull up from 16 feet.

It’s not just star big men who are still allowed, let alone encouraged, to operate in the post; a select class of guards also excels there. In fact, among all players with at least 400 post-ups in the tracking era, while Jokic unsurprisingly leads in points per post-up, guards Jrue Holiday, DeRozan and Booker rank in the top five.

One common factor among Jokic and the guards at the top of that list is that their passing ability makes them immune to an otherwise potent defensive counter to post-ups. In general, post-up efficiency falls against double teams, but as one Eastern Conference analyst said, doubling a guard is a recipe for disaster: It’s too easy for him to find the open man from the middle of the floor.

Even as post-ups have become less common, guards can still hone their craft by studying other physical guards. The veteran DeRozan said he learned from watching Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, as well as Andre Miller and Sam Cassell. And young star Cade Cunningham — who has scored as efficiently in the post as Jokic during his career, albeit in a much smaller sample — said he watches film of big men to study their footwork, plus Holiday because he’s a fellow physical guard who’s «strong as an ox.»

«It’s something that I’ve definitely tried to sharpen in my game for a long time,» the 6-foot-6 Cunningham said. «I got size at my position, so there’s a lot of times I have smaller defenders on me, and it’s an advantage.»

A play designed for mismatches

As analytics have taken root in the NBA, the post-up’s numbers have also improved because teams are finding better situations to call the play. Today’s multiskilled bigs and pace-and-space style allow for more dynamic post patterns than in previous decades.

Victor Wembanyama ranked third in total post touches this season through mid-November, when he suffered a calf strain. But as San Antonio Spurs coach Mitch Johnson noted, Wembanyama’s post opportunities typically come higher up the floor near the elbow, giving him more space to operate and work off the teammates orbiting him on the perimeter.

«Us walking up the basketball and throwing it to him on the low block and everybody staring at him to make everything happen probably isn’t something that we’re [going to do],» Johnson said. «I think sometimes we blur the traditional sense of what we view as a post-up.»

Most teams follow that philosophy in 2025: According to tracking data, a much higher percentage of post-ups start on the move now, compared to a decade ago, while the number that start with a staid, traditional entry pass has plummeted.

«Before, you used to have those go-to plays for post-ups,» Chicago Bulls center Nikola Vucevic said. «And now it’s more so out of the flow, where you set a screen, you roll, you seal your guy, you duck in.»

A push for more post-ups is also a way to get Wembanyama, Vucevic and other centers with shooting range high-value touches against opponents who target them with smaller defenders. Thus, the post-up is a vital tool in the modern big’s belt, because defenses are too savvy about limiting one-dimensional scorers.

«It’s almost necessary for me to be that effective [in the post],» Porzingis said. «I just needed that part. Otherwise, I just would’ve been a pick-and-pop player.»

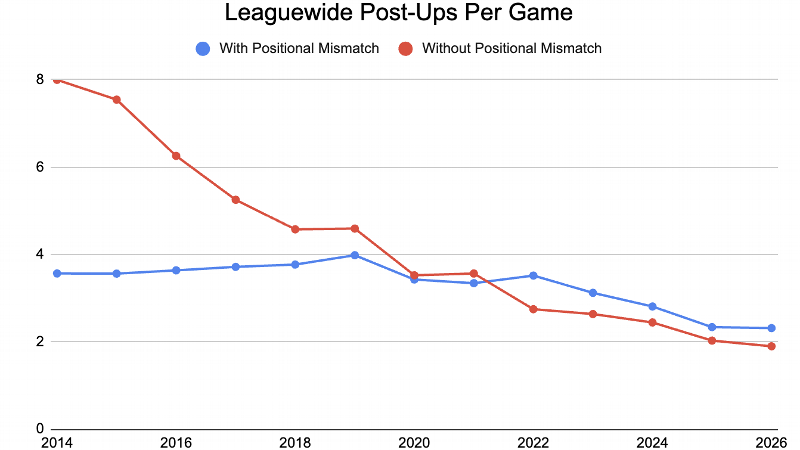

In 2013-14, 31% of post-ups came against positional mismatches — meaning a center or forward posting up a guard, or a center posting up a forward. But the mismatch rate has risen to 55% this season. And extreme mismatches, in which a center posts up a guard, have increased from 1% of all post-ups in 2013-14 to 11% in 2025-26.

Put another way, almost all of the post-ups that disappeared from the NBA were inefficient center-on-center clashes down low.

Jokic, Ivica Zubac and Alperen Sengun were the only players who posted up opposing centers at least 100 times last season, and they all received All-NBA votes. For comparison, a decade earlier, 26 different players reached that threshold, including noncreators such as Kevin Seraphin, Cole Aldrich, Gorgui Dieng and Donatas Motiejunas.

For Porzingis, 57% of his post-ups in recent seasons have come against opposing guards — versus 36% against forwards and only 7% against centers — which even he admits is part of the reason for his best-in-the-league efficiency

«Probably I have to attribute the good numbers and the good analytics to me posting up smaller guys,» he said.

Being able to exploit those mismatches is an important skill, though, as post-ups are a crucial counter to the switching schemes that have grown in popularity across the league. In 2013-14, defenses switched on just 7% of picks, but that number has risen to 24% this season.

«Nowadays, if I do get [a post touch], it’s against a small on a switch,» Sacramento Kings center Domantas Sabonis said.

Sabonis is a gifted scorer and passer, and he explained that without a meaningful post-up threat, offenses can struggle to dictate the course of a possession.

«We’ve had that in the past, where teams switched to get us out of our pick-and-roll game, and then if we can’t convert or get the ball to the big, then it’s a big advantage for the other team,» Sabonis said. «If you can punish them in those areas, they might not do that. It allows the team to still run its offense.»

This relationship points to the second broad lesson of the post-up trend: Strategies aren’t static, and basketball isn’t a solved game. Instead, it’s a cyclical, push-and-pull, act-and-react dynamic.

It’s the NBA’s version of the reason that yards per rush are at an all-time high in the NFL this decade: Because analytically oriented NFL defenses are more concerned about stopping the pass, they concede running room. Schematic battles in sports are all about tradeoffs, so even in a modernized, analytical landscape, there’s still space for traditional tactics to thrive.

«I think as a big man, you should always have a certain post-up game,» Vucevic said, «even if it’s just the basic pivot and hook shot or up-and-under, because you’re going to get them in certain situations. Teams switch a lot more now, and you’re going to have to take advantage of it.»

Vucevic said he tells younger players they should still invest practice time honing those post-up basics, even if they’ve become a less important part of the sport overall. And some team executives agree with these veteran centers. They don’t expect a major uptick in post-up frequency anytime soon. But because so much of modern NBA offense is about attacking mismatches, they view a capable post-up scorer as the «ultimate release valve,» as one Eastern Conference executive said.

Even Carlisle, who once lambasted the post-up as «just not a good play,» understands the post-up’s usefulness in limited doses. Before a game in Chicago last week, Carlisle listed a succession of stars he has coached — Jermaine O’Neal, Dirk Nowitzki, Luka Doncic and Pascal Siakam — and felt comfortable placing in the post.

Siakam is the newest addition to that list, as the Indiana Pacers forward ranks ninth in total post touches this season, en route to a career-high 24.5 points per game. And as one of the most efficient post-up scorers of the past decade, he has a message that encapsulates how the NBA’s remaining post-up aficionados feel.

«I feel like I’m hard to guard in [the post], and I love that coach is trusting me to do that,» Siakam said. «So I’ll keep doing it until they stop me.»